OLS Regression: An ML Classic

Prerequisite Math: Calculus (Derivatives), Introductory Statistics (Expectation, Normal Distribution)

Prerequisite Coding: Basic Python

When we want to use a set of features X, to predict some response Y, one of the simplest (and oldest) approaches is to assume that the predictor-response relationship is linear (ie can be modelled well with a straight line). This approach is intuitive, because our brains deal with linear relationships every day. For example, many people are paid in wages (a linear relation between hours and pay), and most of us at least roughly obey the speed limit (a linear relation between distance and time) while driving. Another benefit of assuming a linear relationship is that the math becomes much more manageable, as we will see shortly.

What is Ordinary Least Squares?

OLS stands for Ordinary Least Squares. We sometimes call this Linear Least Squares, or just Linear Regression. The names come from the fact that we’re choosing our line (the linear model) in order to minimize the sum of the squared errors of our predictions. Why this is a good thing will become clear a bit later. For now, let’s formally define our model. Suppose we have a dataset of n observations, where each observation is a datapoint (x,y). What we’re trying to do is learn the general relationship between the two variables (X and Y). In this post, I will follow the convention of using capitals to denote random variables, and lowercase letters to denote the realizations of those variables. For example, if I wanted to model a linear relationship between height and weight, X and Y would be height and weight generally, while x,y would be specific values (say, 152 cm and 170 lbs). Assuming a linear relationship, our model would take the following form:

\[ y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i + \epsilon_i \]

In this case, the model is simply a sum of three terms. \( \beta_0 \) is the intercept of our line, while \( \beta_1 \) is the slope coefficient. These together make up the line that our model uses to predict new, unseen data. The third term, \( \epsilon_i \) is called the error . It reflects the fact that, on an observation to observation basis, our prediction might be a little bit off. In other words, our line will not pass perfectly through all the points in our dataset. There will be some difference between our predicted value of y, and the true value of y. In this case, we use subscript i, \( i = 1,…,n \) to denote the fact that each observation has its own error, but note that the slope and intercept are constant across all observations. In this model, we call Y the dependent variable, and X the independent variable. This is because we generally want to predict Y given X (not the other way around), and this terminology is used for other models as well. Sometimes, in the regression setting we use the terms regressor and regressand to denote X and Y respectively.

Model Assumptions

We often make additional assumptions on our error term, \( \epsilon_i \). First, we assume that the errors are \( iid \). This means that errors are independent across observations, and that each of the errors comes from the same Data Generating Process (DGP). All this means is that, after accounting for the linear shape of the relationship between X and y, there is no other trend or relationship that we have not accounted for. As we will see later, this assumption is not always realistic. We also assume that errors are mean zero. In other words, our predictions will be perfect on average. Consider, for a moment, if the errors were not mean zero. If errors had an average value of say, 2, we could simply add 2 to our intercept and force the errors down to zero mean!

The case described above is called simple linear regression, because we are only studying the relationship between Y and one other variable, X. We can generalize the math above to account for multiple independent variables (indeed, we will do so later). When this happens, the model takes the form not of a line, but of a plane (or a hyperplane for > 3 dimensions). But we’ll come back to that later. Regardless of the number of variables, we make one additional assumption about our errors: that they are independent of our regressor(s). Formally, this means that \( E(\epsilon_i|x_i) = 0 \). We call this assumption exogeneity of errors, and it is crucial. If the errors and the regressors were not independent, there would be some way of using X to influence the errors. When trying to find the true relationship between Y and X, we would never be able to isolate X alone, since any changes to X would impact Y both through X directly, and through the error. By definition, we want our error to be unpredictable. If the error were predictable, it would mean our linear model is incorrectly specified, or unreflective of the true Data Generating Process.

How Do We Estimate \( \beta \)?

So we have a model of the population. For this reason, the equation above is called the population regression line, since the true values of Y will include the error terms. However, since in the real world, we will not know what the true error is, our prediction will not account for it. If we knew the true error, we could predict perfectly. All we can do is try to minimize the error, making our predictions as good (on average) as possible. Since our line is fully characterized by the two coefficients \( (\beta_0, \beta_1) \), our question becomes: what coefficient values should we pick to make our predictions as accurate as possible?

Perhaps the most obvious approach is to simply minimize overall error. But what exactly do we mean by this? If we took total error to be the sum of all the errors of individual observations (ie \( \Sigma_i \epsilon_i \)), our underpredictions would cancel with our overpredictions. The negative would cancel with the positive. To correct for this, we can instead try to minimize the sum of squared errors. Formally, we want to choose our coefficients to minimize this value:

\[ \min_{\beta_0, \beta_1} \Sigma_i \epsilon_{i}^{2} \] \[ \Rightarrow \ \min_{\beta_0, \beta_1} \Sigma_i (y_i - \beta_0 - \beta_1 x_i)^{2} \]

This is much clearer. Minimizing the squared error solves our problem of error cancellation, and as we will see shortly, this expression is easy to optimize. Note that there are other formulations that work well (for instance absolute error), but we will stick with this one for the duration of the post. Least Squares is a form of loss function, and most machine learning problems try to obtain predictions by minimizing some loss function across a training dataset.

As mentioned earlier, we can rewrite this math to use vector notation, which is much easier to implement as computer code. Instead of writing our sum of squared residuals with \( \Sigma \) notation, we can write is as a product of matrices:

\[ \min_{\beta} (y - X \beta)^T (y - X \beta) \]

\[ = \min_{\beta} (y^T - \beta^T X^T ) (y - X \beta)\]

\[ = \min_{\beta} (y^T y - y^T X \beta - \beta^T X^T y + \beta^T X^T X \beta ) \]

\[ = \min_{\beta} (y^T y - 2 \beta^T X^T y + \beta^T X^T X \beta ) \]

Note that the last equality here comes from the fact that the middle two terms are identical, since the transpose of a scalar is itself. \( \beta^T X^T y \) has dimension \( (1 \times d) \times (d \times n) \times (n \times 1) = (1 \times 1) \), and \( y^T X \beta \) has dimension \( (1 \times n) \times (n \times d) \times (d \times 1) = (1 \times 1) \) . To account for the intercept term we saw earlier, we add a column of ones to the left side of our X matrix. This ensures that one of the coefficients will simply be a constant.

Now we have an expression we can optimize (minimize). We do this by taking the derivative with respect to \( \beta \), and setting it to zero:

\[ FOC(\beta) \ \Rightarrow \ \frac{d}{d \beta} (y^T y - 2 \beta^T X^T y + \beta^T X^T X \beta) = 0 \]

\[ \Rightarrow -2 X^T y + 2 X^T X \beta = 0 \]

\[ \Rightarrow \hat{\beta}_{OLS} = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T y \]

By solving the above equation, we obtain a closed-form expression for the OLS estimator of \( \beta \). The expression above can be thought of as a function of two matrices: \( X^T X \), which we call the normal matrix, and \( X^T y \), which we call the moments matrix. Notice also that our estimator is only defined if the normal matrix is invertible. What this means is that the columns of the normal matrix must be linearly independent. But, assuming this is not a problem, we now have a closed form expression we can use to program our own regression algorithm.

From Math to Code

To test our algorithm, we will use the python package numpy, which is designed specifically to handle matrix equations. Below, I define a

simple LinearRegression class that allows us to fit a linear regression to a dataset. Once fit, we will also be able to predict on new

values of X. I won’t go through the code line by line, but the comments are easily understood.

# Let's use numpy to help with the computing

import numpy as np

class LinearRegression:

# A class to automate linear regression using both

# analytic and numeric solutions

def __init__(self, X, y):

'''

Object must be initialized with dependent

and independent variables.

'''

n = X.shape[0]

# Add a column of ones

self.features = np.c_[np.ones(n), X.reshape((n,1))]

self.labels = y

def get_features(self):

# Return the array of features (design matrix, n x d)

# print(type(self.features))

# print(self.features.shape)

print('This regression uses {} features'.format(self.features.shape[1]))

return self.features

def get_labels(self):

# Return the array of labels (n x 1 col vector)

return self.labels

# Let's define the analytic solution

def analytic_fit(self):

'''

This method solves for coefficients using the analytic approach.

Requires no input beyond pre-existing attributes of LinearRegression

Output - Just print statements, but attributes will be defined

'''

normmatinv = np.linalg.inv(np.dot(self.features.T,self.features))

mommat = np.dot(self.features.T, self.labels)

# Inverting the inverted cancels itself

self.normal_matrix = np.linalg.inv(normmatinv)

self.moment_matrix = mommat

# Define the coefficients, predictions, and residuals

beta = np.dot(normmatinv, mommat)

self.coefs = beta

self.yhats = np.dot(self.features, beta)

self.residuals = np.subtract(self.labels, self.yhats)

print('------- Regression fitting complete. ----------')

# What happens when we want to predict with new data?

def predict(self, X_new):

'''

Given a new set of features, we want to return predictions.

Input - a design matrix, but no associated labels

Output - An n x 1 array of predictions

'''

new_preds = np.dot(X_new, self.coefs)

return new_preds

Now that we have the algorithm completed, we can use it to walk through an example. We’ll use that same numpy package to

simulate data with a linear relationship. I also add simulated noise, to account for the fact that in reality, the data

will not be perfectly linear.

x = np.arange(100)

eps = np.random.normal(0,5, size = (100,))

y = 5 + 0.5*x + eps

In the above code, I generate simple values of x as the integers between 0 and 100. Then, I construct the values of y using the linear equation we saw above, with an added noise term. Here, I use normally distributed noise, since it is symmetric and mean-zero, but I could have used other distributions (Uniform, Cauchy, etc.). Now that I have data, I can fit our algorithm to it. In this algorithm, I modify X slightly to include a column of ones, so the intercept can be properly calculated. Because I only have 1 feature here, we should expect only two coefficients.

# Define the Lin Reg object

model = LinearRegression(x,y)

# Fit the Regression to the model

model.analytic_fit()

# Print coefficients

print(model.coefs)

------- Regression fitting complete. ----------

[4.07490293 0.5088341 ]

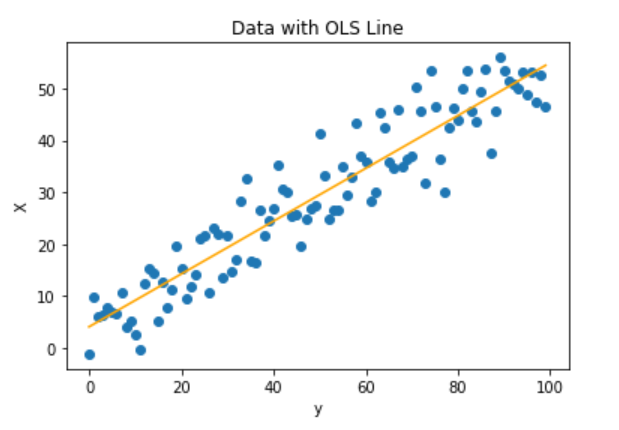

Here the result is our two coefficients (intercept and slope). Notice that the model does a fairly decent job of approximated the true

coefficients (5 and 0.5). So how do we interpret these coefficients? These are the two parameters characterizing the line that

minimizes the sum of squared prediction errors for our dataset (X,y). To further demonstrate this, we can use the matplotlib package

to visualize the line, within the context of our data:

# Plot the data with the regression line

plt.scatter(model.features[:,1], model.labels)

plt.plot(model.features[:,1], model.yhats, color = 'orange')

plt.xlabel('y')

plt.ylabel('X')

plt.title('Data with OLS Line')

plt.show()

We can see from the graph that the line does a great job of representing the true relationship between X and y, given the errors. To predict the value of y for a new value of x, we simply find where on the line our X sits. For larger X values beyond those on the graph, the line is extended.

Properties of the OLS Estimator

Although linear regression is a very simple model that may not always be appropriate for the data, it has some very nice properties. To start, if we take the (conditional) expectation of \( \hat{\beta} \), we get the following result. Note that I’m using vector notation here, for simplicity:

\[E(\hat{\beta} | X) = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T E(y|X)\] \[= (X^T X)^{-1} X^T E( X\beta + \epsilon |X)\] \[= (X^T X)^{-1} X^TX E(\beta|X) + (X^T X)^{-1} X^TX E(\epsilon|X)\] \[E(\hat{\beta} | X) = E(\beta|X) + E(\epsilon|X) = \beta\]The last result comes from the OLS definition (X is orthogonal to the error term). What we’ve just shown here is that the OLS estimate is unbiased, meaning that on average, the estimated value will be equal to the true value of the coefficient(s). Unbiasedness is one of the most desirable properties an estimator can have.

Another closely related property is called consistency. Generally speaking, an estimator is consistent if, as our sample grows infinitely large, the estimator converges in probability to the true value. In more casual terms, consistency is a guarantee that if we get enough data, our estimator will be perfect. Although I will not prove it here, the OLS estimator is, in fact, consistent (I encourage you to try and show this yourself).

Other Extensions

The reason OLS is considered ‘ordinary’ is because there are several extensions to the basic model above, that can greatly improve the ability of regression to predict. The list I show is not exhaustive, but these are considered key extensions. I may write separate posts on one or more of them at a later date.

1. Weighted Least Squares In the above formulation, we assumed that each of our n data observations was equally important. Thus, we gave their errors equal weight in our minimization problem. Under weighted least squares, we can include a matrix of weights that premultplies the design matrix to upweight certain observations relative to others. The solution is very similar to OLS.

2. Generalized Least Squares Another assumption we made above was that our errors were independent, meaning they were uncorrelated. In practice, this assumption does not always hold. Generalized Least squares accounts for this possibility by rescaling the residuals before they are squared and added. This estimator can also be used to account for heteroskedasticity (non-constant variance of the errors).

3. Non-linear Least Squares This is another generalization where, although we still minimize the sum of squared errors, we no longer assume the prediction-response relationship is linear. Since the solution in this case is often not available in closed form, numerical methods are often used to iteratively optimize the error surface.

4. Regularized Regression How do we avoid extremely large coefficients? One option is to minimize LS error subject to a constraint on the total sum of the parameters (coefficients) of the model. This is called regularization, and in some cases, it can also be used for model selection. What we usually do is add to the LS equation by including a penalty term, which increases in the size of the parameters. By minimizing this new equation, we force the parameters on the unimportant variables to shrink.

Further Reading

-

From a practical perspective, the text Extending the Linear Model with R by Faraway is a great option.

-

For an economic perspective, and a great treatment of the extension I discuss, you can’t go wrong with the first 3 or 4 chapters of Econometric Theory and Methods by MacKinnon and Davidson.

-

The classic Intro to Statistical Learning with R by Hastie et al. also has a great regression section.