The Effective Simplicity of KNN

Prerequisite Math: Calculus (Derivatives), Intermediate Statistics (Prior, Likelihood, Posterior) Prerequisite Coding: Python(Numpy, Matplotlib)

In today’s post, I’ll talk about one of the oldest and simplest Machine Learning algorithms, called K-Nearest Neighbors. It is a supervised learning technique, meaning in order to use it, we must have a data that is labelled (ie contains human-specified target values for the variable we wish to predict). I’ll go into more detail shortly, but the basic assumption behind KNN is that points similar (close to each other) in feature space should have similar target values. I’ll go through the algorithm in detail, discussing pros and cons while showing a detailed example and providing python code along the way.

The dataset I’ll be using today is the famous (at least among data scientists) Titanic Dataset, which you can find here. The entire dataset contains some data on each passenger (thousands of observations), but since I just want to illustrate the algorithm, I won’t spend much time analyzing or cleaning it. Note than, in practice and in competition, cleaning and engineering your data is probably the most important step, and you should take great care in doing so. To start, I load in the data (I’m using a colab notebook, but any IDE or even the command line would work):

# Load in the data

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

import io

from google.colab import files

uploaded = files.upload()

df = pd.read_csv(io.StringIO(uploaded['train.csv'].decode('latin-1')))

df = df.dropna(axis = 0)

# Take a subset of two columns

X, y = df[['Age', 'Fare']].to_numpy(), df['Survived'].to_numpy()

# X = X[~np.isnan(X).any(axis = 1)]

y = y.reshape((X.shape[0], 1))

print(X.shape)

print(y.shape)

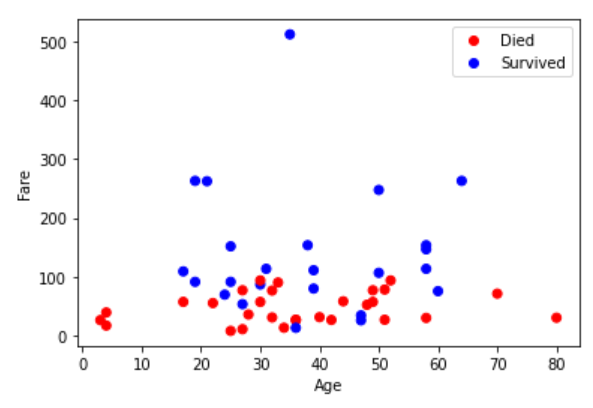

So there’s a few things going on here. First, I load the dataset, which is actually a subset in itself (891 passengers with labels). In our case, there are 11 different features, but with distance-based algorithms, we need numerical features. Since visualizing is easier in 2D, I decided to use just Age and Fare as my two features. Also, I remove any row for which one or more of the feature values is missing (this is true for many of them). In the end, this leaves me with 183 observations (so N = 183), which I convert to numpy array format. Notice that our label is binary (0 = Died, 1 = Survived).

The Algorithm

As mentioned above, the key idea behind KNNs is that points with the same label should be near each other in feature space. To measure nearness, it is common to use a specific distance measure between any two points. So suppose we have a set of features, \( X_{N \times D}\), where \( N \) is the number of data points (rows), and \( D \) is the number of features (columns). You can think of this as a training set, although in K Nearest Neighbors classification, there really is not much training; we just use the existing data to classify new points. Along with our features, we also have class labels, \( y_{N \times 1} \). Suppose we have a new query point (ie one observation of a set of features, or an \( 1 \times m \) vector), and we want to predict it’s class label. The K-Nearest Neighbors classification algorithm does the following:

- Compute the distance between our query point, and each point in the training set (n distances total).

- Select the k-closest points; in other words, select the points corresponding to the k smallest distances.

- Assign to our query point the label that occurs most frequently among the k nearest neighbors.

At its core, that is essentially all there is too it. Simple right? In fact, it’s surprisingly effective despite its simplicity, as we’ll soon see.

The Distance Metric Matters

Now I’ve told you that the K-Nearest Neighbors are chosen by distance to the query point, but I’ve not specified exactly which distance you should use. There’s no right answer here; no distance is proven to be consistently better than any other, but there are a few common choices you might consider. Below I provide the mathematical formula as well as the python code for several common distance functions. For query point \( w \):

Manhattan Distance (also called L1 Norm):

\[\sum_{k=1}^{m} \mid x_k - w_k \mid\]Euclidean Distance (also called L2 Norm):

\[( \sum_{k=1}^{m} (x_k - w_k )^2 )^{1/2}\]Minkowski Distance (a generalization of the two distances above). Note that when \( p \rightarrow \infty \), we simply get the maximum.

\[( \sum_{k=1}^{m} (x_k - w_k )^p )^{1/p}\]Cosine Similarity. This measures the angle between the two data points (as vectors from the origin). Note that the numerator is the inner product of the two points:

\[cos(\theta) = \frac{ X^T W }{ \| X \| \| W \| }\]Note that different distances can lead to different decision boundaries. With a large enough training set, and assuming the training set labels are balanced, this shouldn’t be too much of an issue, but it is worth keeping in mind when predicting new points. The following code computes three of the distances defined above (which three should be apparent). Note that I designed the code to work on numpy arrays, which represent data points as column vectors, but the code can easily be modified for row vectors (transposes).

import numpy as np

# Compute distances for a single query point w, and training point x

# Manhattan distance

def manhattan_distance(x, w):

# Take elementwise differences (should be col vectors)

c = np.subtract(x, w)

# Take the absolute values of differences and sum

d = np.sum(np.absolute(c))

return d

# Euclidean Distance

def euclidean_distance(x, w):

# Take elementwise differences

c = np.subtract(x,w)

# Take sum of squares of differences

d = np.sum(np.square(c))

return d

# Cosine Similarity/Something else

def cos_similarity(x, w):

# Take dot product(numerator)

num = np.dot(x, w)

# Take magnitudes (denominator)

mag_x, mag_w = np.linalg.norm(x), np.linalg.norm(w)

# Construct Cosine

cos = num/(max_x*mag_w)

return cos

In the classification object we will build shortly, we now have the means of using several different distance metrics, which will be helpful in determining how robust our results are.

Don’t Forget to Scale

Before we compute any distance using our data points, it is important to note that it is good practice in any distance calculation to scale the inputs. In our case, we want to normalize each of our features so that they have approximately the same domain. If we do not do this, then one feature containing high numeric values relative to the other columns will dominate the distance computation (and thus the assignment of label to query points), even though there may be other, more important features. For example, if we use population (which is often in the thousands or higher) and number of universities (often a low natural number) to predict the income of a US state, the population will dominate the distances between points, even though the universities clearly matter in determining income. To avoid this, we can subtract each column by its mean, and divide the result by that column’s standard deviation. This process is called standardization, and the code below accomplishes it:

# Scale/subset the data

def scale_features(x):

# Compute mean and standard deviation

m = np.mean(x, axis = 0)

s = np.std(x, axis = 0)

# Standardize the features

z = (x - m)/s

# Return standardized scores and parameters

return m, s, z

Notice that the code above also returns the mean and sample standard deviation of the input dataset. This is intentional - when we split our data into training and test sets later, we want to scale the training and test sets based on the mean and standard deviation of the training set only. This is to avoid what is called data leakage. We do not want any information from our ‘unknown’ data entering the training stage of the algorithm, since this would be equivalent to having access to the future, and we might mistakenly believe our algorithm is better than in reality.

Implementing Prediction

To start, I’m going to consider the case I described above, where we have a single query point. You can think of this as a test set of size one, although later we’ll expand our code to include any arbitrary test set. Our goal here is to product a prediction given the training features and labels, and a query point. The following code accomplishes this:

def KNN_predict_point(X_train, y_train, X_query, k = 3):

'''X_train is (N,D)

y_train is (N,1)

X_query is (D,1)

Result is (1,1)'''

# Scale train features

X_train, m, s = scale_features(X_train)

# Scale test features in an identical way avoids data leakage

X_query = (X_query - m)/s

# Compute distances between train points and query point

d = euclidean_distance(X_train, X_query)

# Extract k closest distances

neighbor_idx = np.argsort(d)[:k]

# Majority vote for label

y_votes = y_train[neighbor_idx]

y_votes, y_counts = np.unique(y_votes, return_counts = True)

# Get most frequent label

max_vote = np.argmax(y_counts)

pred_y = y_votes[max_vote]

return pred_y

You can see that the training and test data are identically scaled. Then the function computes the distance between each training point and the query point. Lastly, the k closest points are identified, and the majority label among them becomes the predicted label. Note that I chose Euclidean distance here, but you could use one of the other distance functions I showed above (or you could write a completely different one if you like). So now we have the ability to predict labels for new query points.

The next step is to generalize this to a larger matrix of query points, ie a test set. This is easily done row by row, since numpy arrays are row-iterable. Here I use a simple for loop, which is not very computationally efficient. However there are ways of speeding up such a computation.

def KNN_pred_multi(X_train, y_train, X_test, k = 3):

# Instantiate list to hold predictions

N = X_train.shape[0]

M = X_test.shape[0]

preds = []

# Generate individual labels for each row

for row in X_test:

preds.append(KNN_predict_point(X_train, y_train, row.T, k = 3))

# Convert list to numpy array

y_hat = np.asarray(preds).reshape((M,1))

return y_hat

Now we’re able to generate an entire vector of predictions. Thus we’re able to analyze the performance of our algorithm on a larger dataset. If you recall earlier, we have such a dataset. I’ll use one of Scikit-learn’s built in splitting functions to split our titanic data into training and test sets. And lastly, I’ll define a simple function that plots our results:

# Plotting Results

from matplotlib.colors import ListedColormap

def plot_classes(features, labels, hues = ['r','b'], classes = ['Died', 'Survived']):

X = features

y = labels

# Color Choices

colors = ListedColormap(hues)

scatter = plt.scatter(x = X[:,0], y = X[:,1], c = y[:,0], cmap = colors)

# Label Axes

plt.xlabel('Age')

plt.ylabel('Fare')

# Generate legend and show plot

plt.legend(handles=scatter.legend_elements()[0], labels=classes)

plt.show()

So now we have everything we need to run our algorithm. The following code simply executes the functions I wrote earlier:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Train test split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 53)

# Generate predictions

y_pred = KNN_pred_multi(X_train, y_train, X_test, k = 3)

# Plot test data and predictions

plot_classes(features = X_test, labels = y_pred)

# Plot Correctness

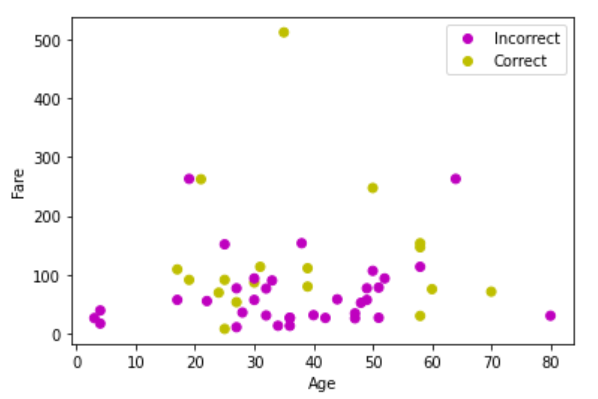

correct_class = (y_pred == y_test).astype(float)

plot_classes(features = X_test, labels = correct_class, hues = ['m','y'], classes = ['Incorrect','Correct'])

The follow plot shows our predictions, along with which points were correctly classified.

There are two things that I notice immediately when looking at these plots (and you should too). The first is that lower fare passengers tended to be the ones who did not survive. We can see that in our test set, virtually every individual labelled as 0 (Did not survive) has a fare below 200. However, the other aspect, which is clearly visible from the right plot, is that our algorithm does not peform very well; very rarely does our prediction match the gold label. So it would be a mistake to conclude that lower fare passengers comprised the majority of those who did not survive, since our predictions are not accurate. How to fix this? Well it could be that the KNN algorithm is simply not a good fit for this dataset. This does happen, and more often than you might think. However, one obvious approach we have not tried is adjusting the size of the neighbourhood in our algorithm. Recalling that k = 3 was the default, how might we determine whether there is a better choice?

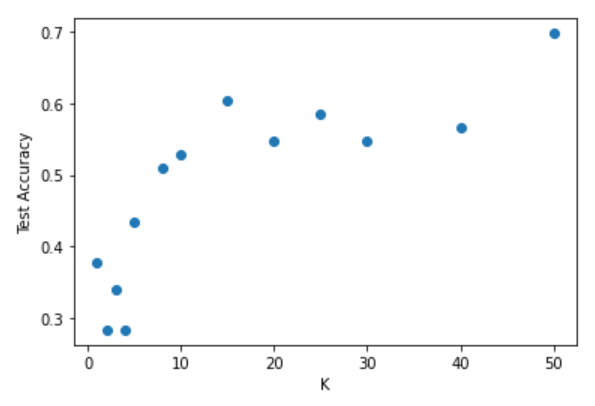

How to Choose K?

The decision boundary we imply for new points depends on our choice of K. Thus K is considered a hyperparameter. How many nearest neighbors do we want? If we choose K to be small, then the boundary will be more flexible. This means that the labels of data points can vary greatly from point to point, and our decision boundary will be very complex (think wiggly). Unfortunately, this also increases our chances of overfitting, where our algorithm may detect patterns that are unique to our data, and have no impact on the true relationship between age, fare and survival status. In statistical terms, we would say that a low value of K leads to high variance, but low bias. Conversely, if we choose a large value of K, then the decision boundary will be much less flexible (closer to a straight line). It will have lower variance, but higher bias, and may underfit (ie be an oversimplification). The key to tuning our model then, is to find the Goldilocks value of K, flexible enough to allow the training data to inform our decision, but not so flexible as to overfit. To find this value, we can simply generate test predictions for a number of values of K, and choose the one that gives the lowest test error. Note that in practice, I would use a third portion of our overall data called a validation set to tune such hyperparameters, but in this case, I’ll just use the test data.

# Choosing K

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

K = [1,2,3,4,5,8,10,15,20,25,30,40,50]

# Instantiate list to hold accuracy scores

A = []

for k in K:

y_pred = KNN_pred_multi(X_train, y_train, X_test, k)

acc = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

A.append(acc)

scores = np.array(A)

# Plot results

plt.scatter(K, scores)

plt.xlabel('K')

plt.ylabel('Test Accuracy')

plt.show()

The above code produces the following plot:

We can see from the plot that the optimal choice of K is near 15. Notice too that there is another maximum at around 60, but this is unlikely to be the best choice, given that our test size is only 53 observations. In fact, choosing a K equal to the size of your data will essentially classify every new query point as the label that most frequently occurs in your data.

Computational Concerns

In terms of computational complexity, the KNN algorithm can be slower than some. Because we have to compute distances between each query point and each training point, the calculation becomes much slower for larger datasets, both in terms of data points (N) and feature space (D). Thus, it is common practice to reduce the dimension of your features before applying such an algorithm. Another option, if you have sufficient data, is to choose a reasonably good label, but not necessarily the exact optimum. In the case above, for binary classification, this is not feasible, but in the regression setting this has been shown to work quite well.

Another option is simply to avoid including large numbers of data points that are both near to each other and identically labelled (this is seen as redundant to a certain extent). Algorithms such as the Condensed Nearest Neighbor use this idea to reduce the size of the training set, and thus speed up the computation.

Watch out for Imbalanced Classes

For a reasonably large choice of K (say 10), it follows that, in order to obtain a reasonably good solution, there should be a non-significant amount of datapoints belonging to each class at any, or at least most locations in feature space. If this is not the case, then the one majority class will dominate predictions of new query point labels even though there significant numbers of other points overall. Thus, for KNN to work well, you should try to aim for as close to perfect class balance in your training set as possible. Obviously this is quite difficult, but there are a number of strategies you might use to try and mitigate class imbalance:

- Try to collect more data

- Make sure you analyze more than just accuracy (e.g. precision, recall)

- Use resampling (targeted to the smaller class)

- Use simulation (approximate real data) to even the classes

Any one of the methods above will give you new data to try and combat the problem of class imbalance. Let me be clear here - a slight imbalance is fine, especially if you have a large dataset. For example, it’s ok if your positive class is one percent of you data if you have over a million observations. But when class imbalance is combined with small sample size, you can get very misleading results if you’re not careful.

The Curse of Dimensionality

So far I’ve shown you a number of ways of computing distances, but the concept of nearness is still somewhat subjective. How can we guarantee that we will have close points in a given dataset? The short answer is you can’t. And it gets worse. The Curse of dimensionality says that the more dimensions you have (more features means more components to your distance), the more likely it will be that any two points you could choose will be far apart along at least one dimension. In other words, the more features we use, the less likely it is that any two features have points close to each other. This is a huge problem for the underlying KNN assumption, since in high dimensions, we may not have any similar points. To show you what I mean, let’s walk through an exercise (this is based on the arguent from Elements of Statistical Learning).

Suppose our data are generated randomly in a uniform hypercube of dimension \( D \). Suppose now we want set our neighborhood to capture some fraction \( r \) of all observations. Since this corresponds to \(r \) percentage of the unit volume, we have that the expected edge length of that neighborhood (in other words, the relative interval of any given feature) is \( r^{1/D} \). In 10 dimensions ( \( D = 10 \)), to capture 1 percent of all points would require an edge length of 0.63, and to capture 10 % would require a length of 0.8. Think about what this means. Given that each feature has a domain of length one in this scenario, we would essentially need to cover 80 percent of the range of each feature to ensure we include just ten percent of our data (on average). Moreover, unless our neighborhood is centered exactly in the middle of the unit hypercube, it is likely that many points will be closer to the boundary than to the middle of the neighborhood, and the distance between two points within a neighbourhood can easily exceed 0.5 (which is half the range of each feature!). This demonstration was just for 10 features, which is actually quite low compared to most industry datasets. The problem gets much worse as D grows.

So what do we make of this? I showed this not to suggest that KNNs or other distance algorithms are bad, but rather to encourage you to take caution in using them. They can perform exceptionally well in certain situations, but are unlikely to in high dimensions without the use of other tricks or complex preprocessing. As with any dataset, you should fit more than one algorithm when attempting to find the best model. Just be aware that for distance-based algorithms, there will almost always be some portion of your data that are far apart along at least one axis of variation.

Conclusion

K-Nearest Neighbors is one of the simplest, most intuitive algorithms there is. As with many of the most popular model choices, there are endless extensions that can be used to improve performance, though I will not go through them here. Overall, here are the key takeways:

- KNNs assumes that points with the same label are near each other

- The Distance Metric Matters

- It can be computationally expensive

- KNNs suffers from Curse of Dimensionality

- Beware class imbalance

Further Reading

- I highly recommend the book Machine Learning: An Applied Mathematics Introduction, by Paul Wilmott. It provides an excellent introduction to not only KNNs, but also most other foundational ML algorithms.

- There is a very detailed section (including the curse of dimensionality argument on which mine is based) in the text Elements of Statistical Learning by Tibshirani et al.

- Blog Sites like Medium likely contain a wealth of knowledge on this algorithm and most others.