The Basic Framework of Reinforcement Learning

Prerequisite Math: None

Prerequisite Coding: None

This post is dedicated to the basics of Reinforcement Learning, which is a subdomain of Machine Learning more generally. Many machine learning techniques involve teaching computers to perform a task by giving the algorithm a series of examples, so the computer can attempt to deduce patterns underlying proper(optimal) behavior. Often (though not always), these examples come with labels made by humans , that allow for evaluative feedback (loss) to guide the machine towards the optimal solution given certain data. However RL operates in a fundamentally different way. Instead of explicitly teaching the computer using human-driven feedback, we give the reinforcement learning agent a direct connection to its environment, so that it may explore possible strategies through trial and error. In this sense, RL agents learn from experience, and from this experience can learn to evaluate the consequences of actions.

Because of the sequential nature of environment exploration, and the fact that the agent can have a very large number of interactions through time, the goal of any Reinforcement agent is simply to maximize a reward signal across time. This brings a number of challenges, since the action of the agent early in time may have a large impact on possible future rewards later. Thus, in evaluating possible actions, the agent must somehow think beyond its current situation. In other words, the agent must plan ahead. So how do we formally define such a framework? Fortunately in the RL community, the notation used to define the components I will go through shortly is fairly universal.

I begin here by defining the action space \( A \), which is simply the set of all possible actions an agent may take. The set of actions can be remarkably simple - for example in the game of tic-tac-toe, which traditionally uses a 3 x 3 board, your action space will be a set of at most 9 choices. Whatever the agent decides at each step in the sequence, it must be that \( a_t \in A \), where \( t = 0, \cdots, T \) denotes current period in the sequence. Note that the action space may change as the agent progresses through time. Also the action space can be continuous or discrete. The tic-tac-toe example is discrete (meaning there are a countable number of choices), but in a different scenario - say, the agent must fly a helicoptor in high winds, or learn to walk - the action space can be continuous, or infinite. Note that the actions available to the agent also depend on what has happened up to the current point in the game. How do we keep track of this information?

Perhaps the most important component in the RL framework is the concept of state. The state contains all the relevent information about what has occurred thusfar. In some cases, this representation is intuitive - the chess board configuration alone is enough for an agent trying to win the game of chess. But in some cases, the state can be quite subtle. An example that comes to mind here is the robotic manipulation task of picking up and putting down a cup. In this case, prior velocity and position from several previous states may be required to fully inform the agent in the current state. The important thing to note is that the state is the mechanism through which the agent interacts with the environment. The state keeps the agent aware of how the game/task changes, which is crucial for understanding the consequences of actions. We similarly denote the state space by \( S \). Sometimes the state space is small too. For instance, in tic-tac-toe there are \( 3^9 \) possible board configurations, many of which are duplicated by symmetry, so the number of states is around 600. However for larger games like Go, or other tasks like learning to walk, the state space can be very large, or even infinite.

Now, in a perfect world, our RL agent would know exactly which action is best in each possible situation that might occur. In general, we call a mapping from state to action a policy, and the goal in any RL task is to find the policy that maximizes reward. We call such a policy the optimal policy, and often denote policies in general with the greek letter \( \pi \). Mathematically, this means \( \pi : X \rightarrow A \ \forall x \in X, \ a \in A \). How exactly the agent deduces the optimal policy is something I discuss later on in the post.

And now for the last fundamental component: the reward signal. One the axioms of reinforcement learning is called the reward hypothesis, which basically says that the objective of any task can be boiled down to a single continuous signal that the agent will try to maximize during its interaction with the environment. In other words, this hypothesis says that the feedback needed to learn the optimal policy in any situation can be expressed as a single continuous number. This might seem controversial, and non-obvious, but while there is still no formal proof that this statement is true, in practice it often holds. For example, in many games, there is often some small, fixed reward amount for most of the game stages, with a large reward (or punishment) occuring only when one player has won (or loss). To be more concrete, you can think of a possible reward function for the game tic-tac-toe, where the agent receives a reward of 1 for an action that results in a win, -1 for an action that results in a loss or draw, and zero for every other action. It becomes clear that only a handful of states will be highly valued, even if the agent learns to think ahead. One of the underlying assumptions I have yet to make clear is that, in the RL setting, the agent only sees the reward after it has chosen the action. Thus, it is only through experience that the agent learns to modify its behavior. Formally, we denote the reward signal, or reward space by \( R \), with the reward generated at each time step \( r_t \in R \). As mentioned above, reward is a scalar.

The Big Picture

The above text contained a lot of new information. Let’s briefly review what we’ve covered. The general RL agent relies on the following components:

- States contain all information about the task/game/learning process up to the current time. The state is an observation the agent receives about the current condition of the environment.

- Actions are the possible choices the agent considers. The set of feasible actions may change depending on the state. In general, the agent wants to choose the action that maximizes potential future rewards.

- Rewards are received by the agent after every action, and provide feedback as to the quality of the choice. The reward is a scalar, and the agent is constantly looking ahead to evaluate the current state and action while balancing immediate and long-term rewards.

- Policy: What the agent is ultimately after is the action at each state that will result in the greatest long-term reward. Such a mapping is called the optimal policy, which can be difficult to find, since the state-action space can be very large.

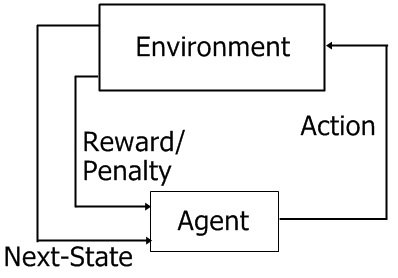

The following picture captures the continual interaction between agent and environment quite nicely, accounting for the order in which each piece of information is received:

So the sequence between agent and environment goes as follows:

- Agent begins in state \( x_t \)

- Agent chooses action \( a_t \)

- Agent receives reward \( r_{t+1} \)

- Agent moves to state \( x_{t+1} \)

In general, beginning at time \( t = 0 \), this generates the following sequence of realizations:

\[X_0, A_0, R_1 , X_1, A_1, R_2, X_2, A_2, R_3, \cdots\]We usually assume some initial state. Sometimes it’s obvious, like a blank checkers board, or the ground/entrance for 3D problems, while other times we can begin in a random state.

Until now, all I have said about the RL agent’s objective is that it involves maximizing long-term reward. What exactly does this mean? Well using the above sequence generated by experience, we end up with a sum of rewards:

\[R_1 + R_2 + \cdots + R_T\]It is exactly this sum of rewards that we want the agent to maximize through its choice of actions. But simply maxizing the sum of rewards above treats future rewards identical to those experienced near the current state. This is certainly not how humans would value future rewards (ie time value of money - all else held constant, you would prefer something today to receiving it tomorrow). And in many cases, we would like our agent to place more weight on current reward than on future rewards. This is accomplished by using a discounted sum of rewards, which we also call the return from a given state:

\[G_t \doteq R_{t+1} + \gamma R_{t+2} + \gamma^2 R_{t+3} + \cdots\] \[\Rightarrow G_t = R_{t+1} + \gamma ( R_{t+2} + \gamma R_{t+3} + \cdots)\] \[\Rightarrow G_t = R_{t+1} + \gamma G_{t+1}\]The above sequence is easily computed, treating \( \gamma \) as a hyperparameter that controls how myopic or near-sighted the agent is. For a finite number time steps, we get that \( G_t = \sum_{t+1}^{T}\gamma^{k-t-1}R_{k} \). Note that the recurrent relation formed makes it easy to start at an end (terminal) state, which would have a return of 0, and work backwards to the current state. This is one of the hallmarks of dynamic programming, which underlies much of the state evaluation we will see soon. But where do these rewards actually come from? Until now, we have assumed that the reward is given to the agent dependent on current state and action, but we can make this relationship more explicit.

Dynamics and Markov Decision Processes

The dynamics of our system refers to the underlying process that controls the transition from one state to the next. The way we typically express the dynamics is by defining a probability distribution that maps current state and action to next state and reward - \( p(x’, r \mid x, a)\). One potential problem you might have considered is that the true probability of arriving at a certain state in the next time step can be incredibly complex. To avoid this problem, we make a simplifying assumption - we assume that the probability of reward and next state depends only on current state and action. This is called the Markov assumption, and it constrains our dynamics to be memoryless; the future now depends only on the present, and not on the past. This assumption might strike you as an oversimplification of reality, but it turns out to work surprisingly well in practice.

Now we have everything we need to define the problem asa Markov Decision Process. An MDP is a 5-tuple ( \( \gamma, X, R, A, P \) ) where:

- \( \gamma \) is the discount factor

- \( X \) is the state space

- \( A \) is the action space (note that the action space may depend on the state)

- \( P \) is the state transition probability matrix that represents the dynamics \( P_{xx’}^{a} = P(X_{t+1} = x’\mid X_t = x, A_t = a)\)

- \( R \) is a reward function, \( R_{x}^{a} = E[R_{t+1} \mid X_t = x , A_t = a] \)

Recall also that we have a given policy \( \pi(a \mid x) \) that maps states to actions. Now we can see that the reward our agent receives is a random variable. This makes it difficult to maximize the return defined above, since there is so much uncertainty (and the return itself is now a random variable). To overcome this, we simply maximize the average, or the expected return. But how does this tie into evaluating a given state? Given our MDP ( \( \gamma, X, R, A, P \) ) and policy \( \pi \):

- The state-value function \( v_{\pi}(x) = E_{\pi}(G_t \mid X_t = x) \) is the expected return beginning at a certain state and following a given policy.

- The action-value function \( q_{\pi}(x,a) = E_{\pi}(G_t \mid X_t = x, A_t = a) \) is the expected return starting from state x, choosing action a and following policy \( \pi \)

These two value functions are what the agent uses to evaluate any given state the agent finds themselves in. Note that the two value functions are related in the following way:

\[v^{\pi}(x) = \sum_{a \in A} \pi(a \mid x) Q^{\pi}(x,a)\]But notice that, in order to compute the above values using their initial formulations, we would need to know all future rewards (or their distributions). Since this is not feasible when the agent is early in the sequence, we can reformulate the value functions using the recurrent relation for return I showed earlier:

\[v^{\pi}(x) = E_{\pi}(G_t \mid X_t = x)\] \[= E_{\pi}(R_{t+1} + \gamma G_{t+1} \mid X_t = x)\] \[= \sum_{a} \pi(a|x) \sum_{x'} \sum_{r} p(x', r | x, a) [r + \gamma E_{\pi}(G_{t+1} \mid X_{t+1} = x')]\] \[v^{\pi}(x) = \sum_{a} \pi(a|x) \sum_{x'} \sum_{r} p(x', r | x, a) [r + \gamma v^{\pi}(x')]\]This last equation is called the Bellman Equation, and it is crucial to the solving of MDP problems, which includes almost all RL problems. The reason it’s so important is because it gives the agent the ability to work backwards from the terminal state (T) and generate values for each previous state. To get a good policy (ie to know which action to choose) the agent just needs to identify the action with the highest value. How exactly we estimate the value function in practice (when the dynamics are not necessarily known) is the subject of another blog post. But for now, just remember that given the final reward and state (which gives the final return), the Bellman equation let’s the agent backtrack through the rollout of states it has taken prior, and generate values for each state it has visited. Given enough repetitions of the task (ie sufficient exploration of the state space), the agent will know which states are desirable, and will update its policy to select actions that take it to those more desirable states.

This concludes the basic framework that underpins most RL problems. Although I did not show it explicitly above, there is a similar Bellman equation for the action-value function (I encourage you to work that out for yourself). What I’ve discussed today is just the tip of the iceberg.

Further Reading

- The canonical RL text is called Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction by Sutton and Barto.

- David Silver has a series of Lectures on RL which are available free online through his personal website.

- Coursera has partnered with the University of Alberta to bring an excellent Reinforcement Learning Specialization.