Prerequisite Math: None

Prerequisite Coding: Python (Functions), HTML (Tags, Classes, IDs)

Scraping Yahoo Finance Data with Python’s Beautiful Soup

In this short post, I’m going to show you how to scrape stock price data using the Beautiful Soup html parser. Since this parser is written in Python, so will be the code that follows (although there are other great parsers for web scraping in other programming languages). Why is it called ‘Beautiful Soup’? Well back in the day (think early 2000s), most html parsers could only interpret well-formed XML or HTML. But much of the web contained more poorly-formed markup (I’m not suggesting the code was written poorly, just that what appears neat to computers does not always appear organized to humans). This was called ‘tag soup’, and the aforeementioned parser was designed to take that soup and make it beautiful.

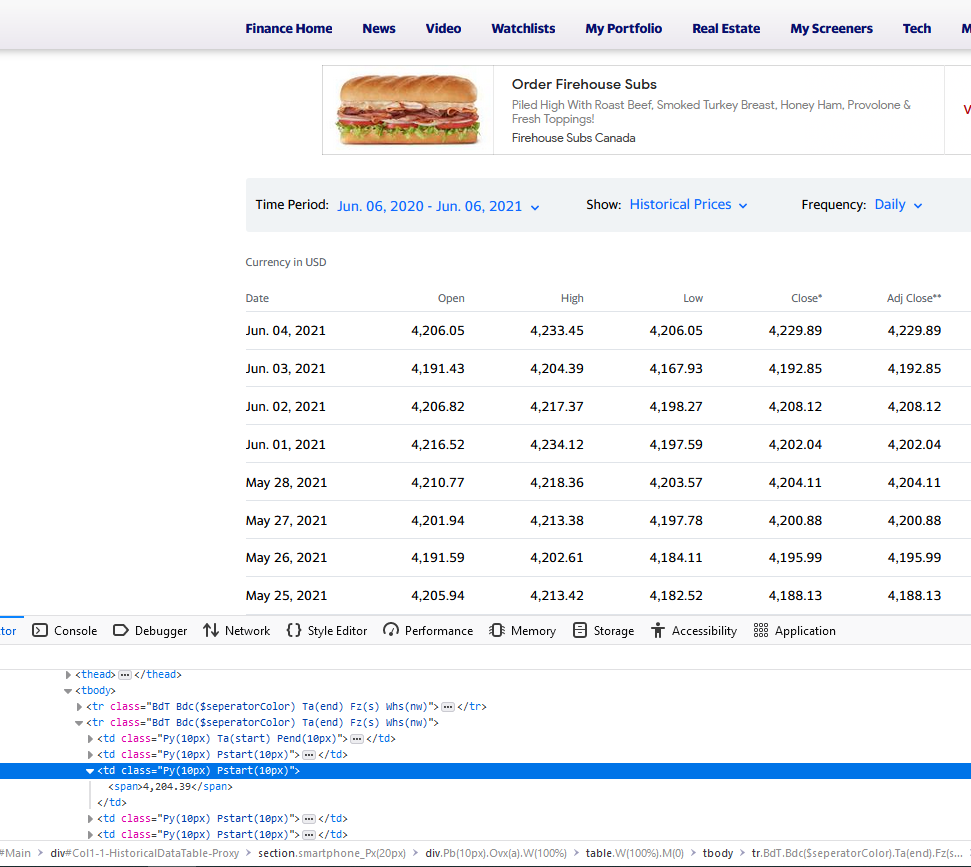

So how does an html parser work? Basically, all code on the internet is written to be read by computers, which means that the information it contains is not easily extracted by humans. HTML parsers are designed to allow users/programmers to extract specific information from a website by specifying particular html tags. You can think of it like a filter designed to separate characters that are used to markup the information from the characters representing the information itself. Let me give you a concrete example. We’ll be extracting stock prices from Yahoo Finance, and these specific prices can be found (buried quite deeply) within the HTML code of the YF website. To see the code itself, most browsers will let you right-click, and select Inspect(Q). In Firefox, for example, you would see a result like the following:

In the top of the image, we see the website as the browser displays it. What we’re interested in here is the tabular data in the center. Below, you can see just how much extra markup language is needed to format the cells in the table. We want to automate the process of extracting the tabular data and removing the markup text. Good news! Beautiful Soup is awesome at this. But before we can extract the information from the markup text, we need a way to automatically download the code in its entirety. For this, we will use the requests library, which allows for simple retrieval via URL. Here is the URL for the image above, which is shows S&P 500 historical data:

Notice the format of the url. We have everything up to the base (‘quote’), and after this, we specify the parameters. In this case, the only thing unique to the S&P 500 is the stock symbol provided at the end. When scraping from a website, it’s common practice to experiment with URL construction by clicking through various pages to see what information is contained in the URLs for that specific site. I’ve already done this for you, so I know that only the stock symbol is needed. For example, to pull identical historical data for Apple (AAPL), I can just substitute the GSPC in the URL above for Apple’s stock symbol. That said, here is the function that constructs the URL. Notice that the only argument is the stock symbol:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

def get_url(stock_symbol):

assert(isinstance(stock_symbol, str))

base_url = "https://ca.finance.yahoo.com/quote/"

url_params = "%5E" + stock_symbol + "/history?p=%5E" + stock_symbol

return base_url + url_params

This function is designed to accept string-type symbols, so I also check for that.

The next function I write is designed to do several steps. Most of these are pretty common:

- I construct the URL using the above function

- Using

requests, I extract the full html content by specifying the URL. - Notice that the table rows I want are marked up using

<tr>tags. I use Beautiful Soup to extract only these tags and their associated information. - There are likely other such tags somewhere on the site. To specify these data tags specifically, I pass the

classargument to the parser. The particular class (as you can see on the image) is"BdT Bdc($seperatorColor) Ta(end) Fz(s) Whs(nw)". - After we extract the HTML, the text is sent to us as a single string (a soup, if you will). I use a list comprehension to select out the information between the relevant tags. The result is a list where every seven observations comprises a row from the table we want.

Here is the function in its entirety. It’s not very complicated, but take few moments to read through each line to see how the code maps to the steps I’ve just outlined.

def get_data_as_list(stock_symbol):

'''Extracts tabular data as a single list of dates and variables.

Data is listed in order, L2R, reverse chronology'''

# Create URL and extract contents

url = get_url("DJI")

page = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

# Find all table column tags with appropriate class

data = soup.find_all('tr', class_ = "BdT Bdc($seperatorColor) Ta(end) Fz(s) Whs(nw)")

# Create list of span tags containing information

data_as_list = [row.select('span') for row in data]

# Extract information

data_separate = [elem.text for row in data_as_list for elem in row]

return data_separate

Now we have all the information we need. There’s just one problem - it’s not very easy to work with. Here is what the current output looks like for Apple (AAPL):

print(get_data_as_list('AAPL'))

['Jun. 04, 2021', '34,618.69', '34,772.12', '34,618.69', '34,756.39', '34,756.39', '270,050,000', 'Jun. 03, 2021', '34,550.31',

'34,667.41', '34,334.41', '34,577.04', '34,577.04', '297,380,000', 'Jun. 02, 2021', '34,614.62', '34,706.65', '34,545.96',

'34,600.38', '34,600.38', '263,810,000', 'Jun. 01, 2021', '34,584.19', '34,849.32', '34,542.87', '34,575.31', '34,575.31', '287,700,000']

The above output is just a fraction of the total return. The true list has about 700 elements. We can see that all the information we’re after is in there, but it’s not easy to see which number matches to which variable. The next function will be used to convert this list into a much more sensible data structure - the pandas dataframe. Such a structure will allow for observation indices and variable names, as well as datatype identifiers, which will make it much easier to subset and analyse the data.

def plot_data(self):

'''Plot each variable'''

df = self.data_as_pandas()

variables = list(df.columns)

df.plot(x="date", y = [var for var in variables if var != "date"])

And that’s it! Writing a series of functions like this is convenient for scraping the prices of different stock companies, but to analyze one company repeatedly, it’s better to define our scraper as its own class. This is called object-oriented programming, and from an engineering perspective, many APIs use this style because it requires less code from the end-user. Here is the code presented as a class:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# This can be done for Yahoo Finance using only the Stock Code

class YahooScraper:

'''Scraping Yahoo Finance Data'''

def __init__(self, stock_symbol):

self.stock_symbol = stock_symbol

def __repr__(self):

print('Historical Stock Data for %s' % self.stock_symbol)

def get_url(self):

assert(isinstance(self.stock_symbol, str))

base_url = "https://ca.finance.yahoo.com/quote/"

url_params = "%5E" + self.stock_symbol + "/history?p=%5E" + self.stock_symbol

return base_url + url_params

def get_data_as_list(self):

'''Extracts tabular data as a single list of dates and variables.

Data is listed in order, L2R, reverse chronology'''

# No sense scraping the same data twice

if hasattr(self, "data_list"):

return self.data_list

else:

# Create URL and extract contents

url = self.get_url()

page = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

# Find all table column tags with appropriate class

data = soup.find_all('tr', class_ = "BdT Bdc($seperatorColor) Ta(end) Fz(s) Whs(nw)")

# Create list of span tags containing information

data_as_list = [row.select('span') for row in data]

# Extract information

data_separate = [elem.text for row in data_as_list for elem in row]

# Remove Commas

data_list = [t.replace(",", "") for t in data_separate]

# Store the list as an attribute

self.data_list = data_list

# Return the list

return data_list

def data_as_pandas(self):

'''Convert data from list to Pandas df.'''

variables = ['date', 'open', 'high', 'low', 'close', 'adj_close', 'volume']

vars_no_date = [var for var in variables if var != "date"]

# No sense making the df twice

if hasattr(self, "df"):

return self.df

else:

# Extract data in list form and convert to array

data = self.get_data_as_list()

data_array = np.array(data)

data_array = data_array.reshape( ( int(len(data)/len(variables)) , len(variables) ) )

# Convert array to pandas df

stock_df = pd.DataFrame(data_array, columns = variables)

stock_df[vars_no_date] = stock_df[vars_no_date].apply(pd.to_numeric)

self.df = stock_df

return stock_df

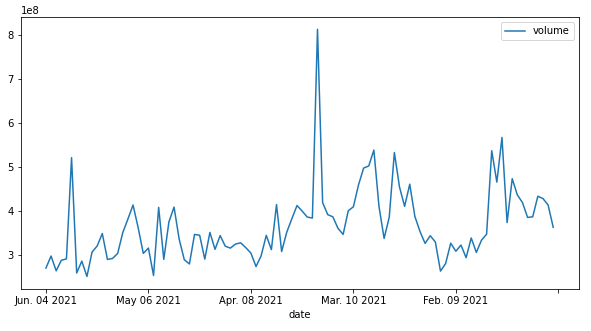

def plot_data(self):

'''Plot each variable'''

df = self.data_as_pandas()

variables = list(df.columns)

df.plot(x="date", y = [var for var in variables if var != "date"])

Think of it like a blueprint for all yahoo scrapers we might want to use. Now all I have to do is define an object of that class, and I can use all the functionality we looked at earlier. Here is the last of the code:

dji = YahooScraper('DJI')

print(dji.data_as_pandas())

print(dji.plot_data())

Just 3 lines of code if I want to use this scraper repeatedly. Here is the output of those 3 lines:

date open high low close adj_close volume

0 Jun. 04 2021 34618.69 34772.12 34618.69 34756.39 34756.39 270050000

1 Jun. 03 2021 34550.31 34667.41 34334.41 34577.04 34577.04 297380000

2 Jun. 02 2021 34614.62 34706.65 34545.96 34600.38 34600.38 263810000

3 Jun. 01 2021 34584.19 34849.32 34542.87 34575.31 34575.31 287700000

4 May 28 2021 34558.50 34631.11 34520.09 34529.45 34529.45 290850000

.. ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

95 Jan. 19 2021 30887.42 31086.62 30865.03 30930.52 30930.52 386400000

96 Jan. 15 2021 30926.77 30941.98 30612.67 30814.26 30814.26 433000000

97 Jan. 14 2021 31085.67 31223.78 30982.24 30991.52 30991.52 427810000

98 Jan. 13 2021 31084.88 31153.37 30992.05 31060.47 31060.47 413250000

99 Jan. 12 2021 31015.01 31114.56 30888.76 31068.69 31068.69 362620000

We get the dataframe itself, as well as plots of all the variables. You can see how this would be useful for examining the history of many different stocks.

Some Caveats

Let me start by saying that web scraping itself is not illegal. However, automated querying of servers to retrieve HTML from web pages can cause serious damage if increased server traffic overloads a site’s capacity. If the site is commercial in nature, careless scraping could lead to lost revenue, depending on the situation. With this in mind, there are some best practices I recommend you follow:

-

Check to see if the site has an API. Yahoo Finance used to have an API, which is an interface designed to give programmers controlled access to Yahoo’s raw data. As of 2017, this API is no longer current, but in general you should use an API if one exists. Only in cases where there isn’t one should you consider scraping.

-

Use a slow crawl rate, and try to scrape during off-peak hours. To a web server, requests from a scraping program are no different than those of a point-and-click user. The difference is that the program can send hundreds or even thousands of requests per second, which has the potential to overload a web server. This can disable a website, and is called a Denial of Service(DoS) attack, and is a very effective tool used by malicious hackers. If you are just scraping data for research purposes, be kind and space out your requests. Some sites may explicitly state a preferred crawl rate (1 per 5 seconds is common). Try to adhere to this.

-

Take only what you need. In this post, I thoroughly inspected Yahoo’s webpage to learn the exact URL containing the data I wanted. In the end, I only made one request. Wasteful scraping bots may crawl through URLs searching for useful information, but if you prepare ahead of time, you can be much less burdensome.

-

Avoid re-querying the same thing. In the OOP code, I insert some logic to avoid having to re-request the same information. This is not only kinder to the website, but is computationally much faster than having to wait for a response over-and-over again. This is even more important for larger scraping projects, where a single request can take minutes.

Conclusion

So now you know how to use Beautiful Soup to extract information from websites. This is an incredibly useful skill to have, since most new data first appears online. But with great power comes great responsibility. Be kind to the owners of the pages you scrape.

Further Reading

- Here is another excellent tutorial on Beautiful Soup.

- The Documentation for the package is suprisingly readable, and very helpful.

- On my home page is a draft (incomplete) of a paper I’m working on that provides ethical and effective scraping principles.