Prerequisite Math: Calculus

Prerequisite Coding: Python (Numpy)

Building a Neural Net Using Just Numpy

I remember reading an article the other day about how someone had attempted to make a BLT completely from scratch. They milked the cow, grew the lettuce and tomato, and even butchered their own bacon. They made their own mayonnaise, and baked their own bread. When all ways said and done, the price of making that sandwich by hand turned out to be well in excess of 1000 dollars. This is shocking to some, given that you can buy a BLT from many sandwich shops for about 8 dollars as of the writing of this post. This is because advances in technology bring significant cost reductions, that people often take for granted.

Many ML practitioners take a similar view when building models. Using state of the art frameworks like pytorch, tensorflow, and keras, it can seem like building

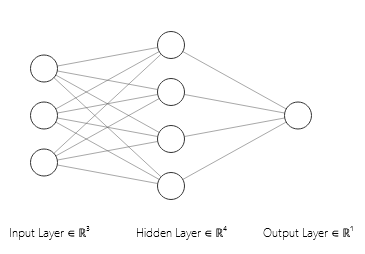

deep learning models is just a matter of typing a handful of lines of code. With so much of the process fully automated, one can lose sight of what actually goes on under the hood. With this in mind, I’m going to build a simple neural net from scratch, relying only on python’s numpy package to store and manipulate arrays. The network itself is just a simple 3-input, 1-output model with one hidden layer. Here is a picture:

You can see that I’ve used a single hidden layer with 4 nodes. Now before I write a single line of code, I’m going to make sure I have all the equations for the network mapped out. I’ll also make sure I know the dimensions for each parameter (or parameter matrix), since dimension errors are one of the most frequent bugs found in deep learning code. To begin, let me define a few quantities of interest:

\(N\) (note the capitalization) is the number of data points we have. When training the network, this will be the size of our training set.

\(D\) is the number of features we have. This corresponds to the number of nodes in our input layer, and is also the number of columns in our training set.

\(n_h\) is the number of nodes in our hidden layer. This is the middle layer of our network, and we can see from the picture that \( n_h = 4\).

Our Data

Today is less about achieving state of the art results, and more about building the network. With this in mind, I’ll use the famous Boston Housing Dataset, which uses 13 different features to try and predict median home value in 506 different suburbs of Boston. For this demonstration, I’ll just use three features: Property tax per 10,000 dollars, average pupil-teacher ratio, and crime-rate per capita. The labels are listed in thousands of dollars. Here is the code for loading and extracting the features and labels. I also define some parameters we’ll use shortly.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import load_boston

features, labels = load_boston(return_X_y = True)

# Take only three features, and the labels

X0 = features[:,[0,9,10]]

X0 = X0/np.max(X0, axis = 0)

t = labels.reshape((labels.shape[0],1))

print(X[:5])

print(t[:5])

# Create activation function

def relu(x):

return (x > 0)*x

With the data prepped and parameters chosen, let’s look at how to code the network itself.

Vector Operations

As I mentioned above, we have only one hidden layer. Here are the equations that govern the network, with \( X_0 \) representing our raw data, which has dimension (\( N, D \) ):

\[Z_1 = X_0 W_1\] \[X_1 = Relu(Z_1)\] \[y = X_1 W_2\] \[L = \frac{1}{2} (y - t)^2\]Pretty simple right? Note that I have removed any bias terms that you might see in other networks (just for simplicity). Now in order to derive the dimensions for the weights, we can first get the dimensions of our inputs and outputs, then work between them. Let me show you what I mean. I know (by definition) that our data must have dimension equal to the number of observations (rows) by the number of features (columns). Thus, \( X_0 \in (N, D) \). I also know that the dimension of the hidden layer’s input just converts from feature space (3) to hidden-layer space (4), so it must be that \( X_1 \in (N, n_h) \). Knowing that the Relu activation works elementwise (does not change the dimension), it must be that \( W_1 \in (D, n_h) \), otherwise the dimensions would not match. In any dot product, the columns of the left matrix must equal the rows of the right matrix.

Similarly, we can deduce the dimensions of the other variables:

\[X_0 - (N, D) \ , \ W_1 - (D, n_h)\] \[Z_1 - (N, n_h) \ , \ X_1 - (N, n_h)\] \[W_2 - (n_h, 1) \ , \ y - (N, 1)\]Now that we have the equations to follow, and the dimensions are computed, we can code the forward pass of our network. The code for this is below.

## Forward Propagation

def forward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2):

'''Computes the forward propagation of the

network and stores parameters.

X0: the training data (N,D)

t: the labels (N,1)

W1: 1st weight matrix (D,n_h)

W2: 2nd weight matrix (n_h, 1)'''

# Run through network per equations given

Z1 = np.dot(X0, W1)

X1 = relu(Z1)

y = np.dot(X1, W2)

# Compute and print error (MSE)

error = np.sum(0.5*(y - t)**2)

print('Error: ', error)

print('---------------')

# Return values

return X1, y

Backward Propagation

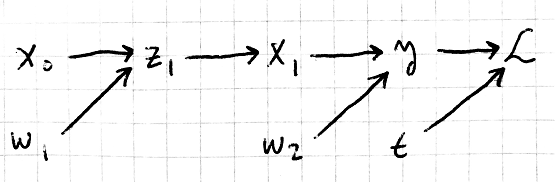

The backpropagation step requires that we attribute the overall change in our loss (error) to each of the weights. In order to do this, we need to know how sensitive is our loss to changes in each weight. In other words, we want to compute the derivatives with respect to our two weight matrices ( \( W_1, W_2 \) ). We do this by using the chain rule. But there are many relationships to keep track of, even in this simple network. To keep things organized, and to help with derivative computation, I like to turn our equations into a computation graph. This is a structure that identifies all the relationships in our network, and here is what ours looks like:

There aren’t a lot of free computation graph illustrators, so I just drew this one by hand. But beyond showing the relationships in our network, such a graph is very useful for computing derivatives using the chain rule. One of the more interesting aspects of coding up a neural network is that we don’t need closed expressions for each derivative, we only need rules for computing the derivatives we care about. What does this mean exactly? Well, suppose we want to compute the derivative of the loss with respect to the first weight matrix, \( W_1 \). You can see there are a lot of intermediate variables whose derivatives we would need to find first. Instead of combining all these individual relationships to get a closed-form expression for the derivative we want, we work backwords through the graph. Start with loss, and take its derivative only with respect to variables connected to it (ie the variables whose arrows point to it). Once we’ve computed those, we move one level backward, taking the derivative of y w.r.t the variables connected to it, and so on and so forth. Here’s how this looks when done on the whole graph. Note that \( t \) is our labels, also called targets, which aren’t really variables, since they will not change. So I don’t bother with that derivative.

\[dL = \bar{L} = \frac{dL}{dL} = 1\] \[dy = \bar{y} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} = (y - t)\] \[dx1 = \bar{X_1} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial X_1} = (y - t) W_2^T = \bar{y} W_2^T\] \[dw2 = \bar{W_2} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial W_2} = X_1^T (y - t) = X_1^T \bar{y}\] \[dz1 = \bar{Z_1} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial X_1} \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial Z_1} = I(Z_1 > 0) \bar{X_1}\] \[dx0 = \bar{X_0} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial X_1} \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial Z_1} \frac{\partial Z_1}{\partial X_0} = \bar{Z_1} W_1^T\] \[dw1 = \bar{W_1} = \bar{Z_1} \frac{\partial Z_1}{\partial W_1} = X_0^T \bar{Z_1}\]Perfect! We now have the derivatives we need to perform backpropagation. I typically use the ‘bar’ notation you see above to express pieces of the chain in a longer derivative. Notice also apart from the first two derivations, we never needed to express any of these derivatives in their full form. Not only is this easier when deriving these with pen and paper, but it is also faster computationally. I actually computed more derivatives than we needed here, but I just wanted to stress the advantage of using the computation graph.

You might be wondering why I used the matrix transpose in certain places, and how I knew when to do this. One very helpful rule of thumb is that the matrix of derivatives must have the same dimension as the variable itself. For example dx1 must have the same shape as \( X_1 \), dw2 the same shape as \( W_2 \), and so on. So I use the transpose wherever it is needed to preserve the dimension. When we execute backprop, even though we only need the derivatives of the weights (since they are what is being updated as the network learns), preserving the shape across all intermediate variables is good practice.

Here is the code for backpropagation:

def backward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2, X1, y):

'''Computes the backward propagation of the

network and returns the updated weights.

X1: The data in the hidden layer (N, n_h)

y: The predicted target (N,1)'''

# Compute derivatives shown above

dy = (y - t)

dX1 = np.dot(dy, W2.T)

dW2 = np.dot(X1.T, dy)

dZ1 = (Z1 > 0)*dX1

dX0 = np.dot(dZ1, W1.T)

dW1 = np.dot(X0.T, dZ1)

# Update the weights

W1_new -= alpha*dW1

W2_new -= alpha*dW2

# Return updates

return W1_new, W2_new

Numpy makes it very easy to take the derivative expressions we found earlier and turn them into code. Notice that although the function above takes several arguments, the only two that change are the two weight matrices. Also included in the backprop function are the update rules for the weights. Though these are sometimes included separately, in this case I just state them with backprop. The update rules are very intuitive: think of the derivatives (gradients) as marking the direction of greatest increase on our loss curve. We want to change the weights so that they go in exactly the opposite direction (hence the negation), and decrease by our step size (alpha).

Dropout

Now you may be thinking to yourself, isn’t a neural network a bit complex for this simple dataset? Don’t housing price and property tax follow a roughly linear relationship, and thus wouldn’t linear regression be a perfectly adequate model choice? Well you’re right; if we’re not careful, the complexity of the neural network may lead to bad performance. With this in mind, we want to try and avoid overfitting to our data. When this happens, the model is identifying patterns between our features and median value that coincidentally occur in the data we have, and are not true for these relationships in general. In other words, the model just memorizes our data, and will not generalize very well to unseen data. It may mistakenly conclude that one particular node in our network is very important, even though better predicting features lie elsewhere. So how do we prevent the network from overfitting to one particular feature or node?

Well one of the most popular approaches is called dropout. In dropout, every time a data point passes through the network, we randomly ‘shut off’ or ‘drop out’ one or more of the nodes (we set those corresponding weights to zero), so that the network is forced to try and learn how to predict without that particular feature. This has the effect of making our network much more robust to outlying data points, and usually improves performance. Here is the code for dropout, which takes as input a weight matrix, and randomly switches off some of its weights:

def dropout(W, p):

''' Randomly shut off p proportion of

weights in a weight matrix. '''

# Capture initial shape for later

l = W.shape[0] # length

d = W.shape[1] # width

# Flatten Matrix

flat_weights = W.flatten()

# How many obs to set to zero?

drop_num = np.floor(len(flat_weights)*p)

# Generate random indices

drop_idx = np.random.choice(len(flat_weights), size = (int(drop_num),1),

replace = False)

# Turn off some nodes

flat_weights[drop_idx] = 0

# Reshape weight matrix

W_new = flat_weights.reshape((l,d))

return W_new

All I have to do to actually implement dropout in our network is pass through our weight matrices as arguments in the forward pass, and this will have the effect of nullifying a different series of weights every time. With this in mind, the forward pass code needs a slight revision to account for this:

def forward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2):

'''Computes the forward propagation of the

network and stores parameters.

X0: the training data (N,D)

t: the labels (N,1)

W1: 1st weight matrix (D,n_h)

W2: 2nd weight matrix (n_h, 1)'''

# Implement Dropout on W1 and W2

W1 = dropout(W1, prob)

W2 = dropout(W2, prob)

# Run through network per equations given

Z1 = np.dot(X0, W1)

X1 = relu(Z1)

y = np.dot(X1, W2)

# Compute error (MSE)

error = np.sum(0.5*(y - t)**2)

# Return values

return X1, Z1, y, error

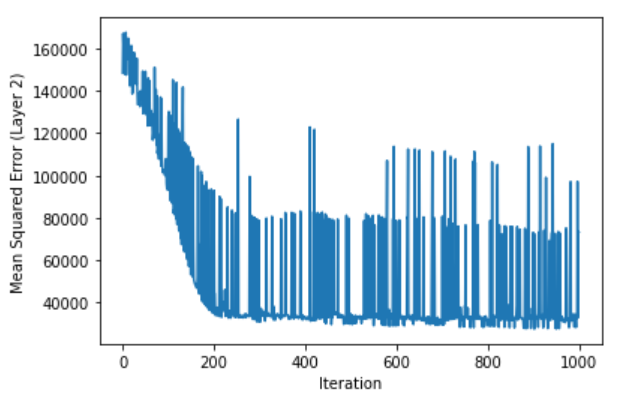

Excellent! We’re nearly there. One last thing that might be bothering you - how will we know our network is working? How do we really know we’re reducing the error? One easy way is to simply keep track of that error every iteration. Plotting it should show you that your error is reducing. To deal with this, I write a simple plotting function using matplotlib:

def plot_error(errors):

'''Create a plot of the errors by iteration'''

x = np.arange(n_iter)

y = np.array(errors)

plt.plot(x,y)

plt.xlabel('Iteration')

plt.ylabel('Mean Squared Error (Layer 2)')

plt.show()

Alright, that’s all the prep functions we need. Now all we have to do is iterate through the foreprop and backprop steps to train the network. Here is that code:

###### Train the network ######

# Define parameters

N = X0.shape[0]

D = X0.shape[1]

n_h = 4

n_iter = 10

alpha = 0.000001

prob = 0.2

# Initialize weight matrices (random -1 to 1)

W1 = 2*np.random.random((D, n_h)) - 1

W2 = 2*np.random.random((n_h, 1)) - 1

# Keep track of errors

errors = []

# Set number of iterations

n_iter = 1000

# Training loop

for iteration in range(n_iter):

# Run a forward pass

X1, Z1, y, error = forward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2)

errors.append(error)

# print error every 10 iterations

if iteration %10 == 0:

print('Error: ', error)

print('---------------')

# Run a backward pass to update weights

W1, W2 = backward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2, X1, Z1, y)

This code should be fairly self explanatory. What we’re doing first is setting parameters, and initializing weight matrices to be between -1 and 1. Feel free to play with the parameters to see how this changes the error. Next I set the number of iterations, making sure to keep track of the error using a simple list. Then for each iteration, I run forward and backward passes, updating the weights using the gradients, and storing the error along the way.

Visualization

All I do to plot the errors is execute the function I wrote earlier:

plot_error(errors)

This gives the following plot:

We can see from the plot that error is indeed decreasing. I should say that this plot is very volatile - normally we might expect to see smoother descent. What’s going on here? Well, there are a number of reasons why the network has difficulty finding the minimum error. Here are a few:

-

The median value variable appears to be truncated, meaning that its highest values have been artificially shrunk to some ceiling. Thus the network is not seeing the entire relationship between features and response.

-

For illustrative purposes, I’ve only chosen 3 features of the 13 available. This dataset is very well engineered, meaning each of the features has strong predictive power on the value of housing. This means that there are cases where our 3 features are not necessarily behind a high (or low) value, so the network has trouble adjusting.

-

We did not give the network very many observations. 500 observations may seem like a lot for a regression model, but given the complexity we can bring with a neural network, it is not uncommon to train such nets on millions of data points.

Let me also note that, if I were trying to maximize performance of this network (as would be the case for a real-world intelligent system), I would now go through several rounds of hyperparameter tuning, experimenting with all the default settings I provided above. I encourage you to do this. I would also try and estimate some sort of test error, either using cross-validation (the subject of a later post), or by setting aside some of the observations to test the network after training is finished. Training error by itself usually overestimates an algorithms performance on unseen data.

Conclusion

Here is the code in its entirety:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import load_boston

features, labels = load_boston(return_X_y = True)

# Take only three features, and the labels

X0 = features[:,[0,9,10]]

X0 = X0/np.max(X0, axis = 0)

t = labels.reshape((labels.shape[0],1))

print(X[:5])

print(t[:5])

# Create activation function

def relu(x):

return (x > 0)*x

# Create Dropout Function

def dropout(W, p):

''' Randomly shut off p proportion of

weights in a weight matrix. '''

# Capture initial shape for later

l = W.shape[0] # length

d = W.shape[1] # width

# Flatten Matrix

flat_weights = W.flatten()

# How many obs to set to zero?

drop_num = np.floor(len(flat_weights)*p)

# Generate random indices

drop_idx = np.random.choice(len(flat_weights), size = (int(drop_num),1),

replace = False)

# Turn off some nodes

flat_weights[drop_idx] = 0

# Reshape weight matrix

W_new = flat_weights.reshape((l,d))

return W_new

## Forward Propagation

def forward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2):

'''Computes the forward propagation of the

network and stores parameters.

X0: the training data (N,D)

t: the labels (N,1)

W1: 1st weight matrix (D,n_h)

W2: 2nd weight matrix (n_h, 1)'''

# Implement Dropout on W1 and W2

W1 = dropout(W1, prob)

W2 = dropout(W2, prob)

# Run through network per equations given

Z1 = np.dot(X0, W1)

X1 = relu(Z1)

y = np.dot(X1, W2)

# Compute error (MSE)

error = np.sum(0.5*(y - t)**2)

# Return values

return X1, Z1, y, error

## Backward Propagation

def backward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2, X1, Z1, y):

'''Computes the backward propagation of the

network and returns the updated weights.

X1: The data in the hidden layer (N, n_h)

y: The predicted target (N,1)'''

# Compute derivatives shown above

dy = (y - t)

dX1 = np.dot(dy, W2.T)

dW2 = np.dot(X1.T, dy)

dZ1 =(Z1 > 0)*dX1

dX0 = np.dot(dZ1, W1.T)

dW1 = np.dot(X0.T, dZ1)

# Update the weights

W1_new = W1 - alpha*dW1

W2_new = W2 - alpha*dW2

# Return updates

return W1_new, W2_new

# Plot errors during training

def plot_error(errors):

'''Create a plot of the errors by iteration'''

x = np.arange(n_iter)

y = np.array(errors)

plt.plot(x,y)

plt.xlabel('Iteration')

plt.ylabel('Mean Squared Error (Layer 2)')

plt.show()

##### Train the network #####

# Define parameters

N = X0.shape[0]

D = X0.shape[1]

n_h = 4

n_iter = 10

alpha = 0.000001

prob = 0.2

# Initialize weight matrices (random -1 to 1)

W1 = 2*np.random.random((D, n_h)) - 1

W2 = 2*np.random.random((n_h, 1)) - 1

# Keep track of errors

errors = []

# Set number of iterations

n_iter = 1000

# Training loop

for iteration in range(n_iter):

# Run a forward pass

X1, Z1, y, error = forward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2)

errors.append(error)

# print error every 10 iterations

if iteration %10 == 0:

print('Error: ', error)

print('---------------')

# Run a backward pass to update weights

W1, W2 = backward_pass(X0, t, W1, W2, X1, Z1, y)

plot_error(errors)

Now I have some rather depressing news - apart from the code we used to import and preprocess the data, this entire network can be written in about 4 lines of keras code. Most of the nuts and bolts i’ve just shown you have been fully automated, and can be used right out of the box. Automatic Differentiation now means we never actually have to compute derivatives or run backprop ourselves. This really makes you appreciate how far the machine learning community has come in bringing flexible ML APIs to most of the world. However, I’m a firm believer that although these frameworks are a great thing - most of my future deep learning posts will probably use one or more such frameworks - there is still tremendous value in knowing what’s going on under the hood. I would argue that, just like building that BLT from scratch would give you much better insight, until you can build a network like this from scratch, you’ll never be able to get the most out of todays state-of-the-art software.

Further Reading

- I love the Grokking series of computer science books, and Deep Learning, by Andrew Trask, inspired me to build this NN from scratch.

- Goodfellow et Al have a great Deep Learning textbook that deals with the math behind backpropagation quite well

- I recommend the DeepLearning.ai deep learning specializations on Coursera. I’ve completed a few of them myself, and they’re great for those (like me) who lack the formal CS background.