Prerequisite Math: Big-O Notation

Prerequisite Coding: Python (Classes and Methods)

Comparing Arrays and Linked Lists in Python

In today’s post, I’m going to be talking about two fundamental data structures used in computer science: arrays and linked lists. I’ll explain what each is, what advantages each has compared to the other, then we’ll code each of these structures in python. Even though python has basic structures in place that very much resemble what I’m about to show, I find it’s very good practice to implement these yourselves. Doing so helped me understand them when I first learned about data structures and algorithms.

The Array

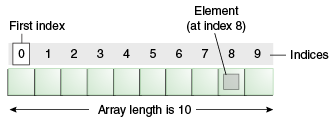

Let’s start with a metaphor. Suppose you and your friends are trying to find seats for a hockey game. The memory of a computer looks a lot like the arena seats you and your friends would search for - a series of blocks (seats), each able to store one item (seat one person), and each block/seat having a unique address. And just like a computer storing information, there are a number of ways you and your friends might choose where to sit. An array is a method for storing information that uses contiguous (sequential) slots. In this case, this means that you and your friends all sit side-by-side. What’s unique about an array is that each position is numbered. In one dimension, this means that each position is given an index from left to right. Be warned, in many languages, this starts at zero, not at one (python is zero-indexed). Because the array is a set of continuous blocks, the size must be defined before any items are placed in memory. This means you choose how many seats to reserve before you and your friends show up on game day.

Why index every position? Well this makes it very easy to find any element in the array (by index). For example, what if we want to find the 5th element in the array? The general formula for finding the i-th element is:

\[array\_address + elem\_size \times (i - first\_index)\]The only information we need to completely specify the array is the address of the first element, and the array size. In the above formula we also need the element size, but this is usually 1 (1 item per slot in memory). Some rare applications may require you to sum up different sizes to find items later in the array, but for now we just assume, like the indices, that each item has 1 slot. So to find the 5th item, we look in position 0 + 1*(5-1) = 4. Thus, index 4 contains the 5th item in our array. In general, arrays are very good at reading or retrieving items, thus the read operation using arrays is \( O(1) \). What about adding an element to an array? Typically items are added from left to right. Adding an item to a list is called pushing, and removing an item is called popping.

What happens if we want to add an item to the back of an array? As long as the array is not full, that’s no problem. We just assign our new item to the earliest open slot allocated to the array. Thus, back insertion is \( O(1) \). What about adding to the front? Remember, every item in our array is indexed, so adding to the front involves re-indexing (moving) every item already in the list. In the worst case, this operation is \( O(N) \). For deletion, we have a similar story. Deleting from the back is no problem - this is \( O(1) \). But from the front, we run into the same problem. When the first element is removed, all remaining elements drop one in index. This involves computation on every element in the array, which is \( O(N) \).

One last problem with arrays is that in order for them to be defined, there must be an available sequence of memory slots equal to or greater than the size you request. For an array of size 10, this is not likely to be an issue, but for arrays with hundreds of elements, it could be that the array just won’t fit. So in some sense, this structure is only feasible in certain situations. So how can we implement this in python? Unfortunately python does not have its own version of an array (though the list data type is very similar), but we can define our own. Here is a simple array class, that accepts size as an initialization parameter:

class Array:

''' An array data structure '''

def __init__(self, size):

# instantiate the empty array

self.array = []

self.length = 0

self.size = size

def __repr__(self):

return '{}, array of length {}'.format(self.array, self.length)

def push_back(self, elem):

''' add an element to the back of the array '''

if self.length == self.size:

raise Exception('Array is full')

self.array += [elem]

self.length += 1

def push_front(self, elem):

''' add an element to the front of the array '''

if self.length == self.size:

raise Exception('Array is full')

new_array = []

new_array += [elem]

for elem in self.array:

new_array += [elem]

self.array = new_array

self.length += 1

def pop_back(self):

''' Remove last item from list, and return it'''

if self.length == 0:

raise Exception('Sorry, nothing to pop')

# Get the last item

pop_elem = self.array[-1]

# Instantiate new array

new_array = []

# add all but last items to new array

for elem in self.array[:-1]:

new_array += [elem]

# Change old array to new array

self.array = new_array

# Modify length

self.length -= 1

# Return popped element

return pop_elem

def pop_front(self):

''' Remove and return the front element for the list '''

if self.length == 0:

raise Exception('Sorry, nothing to pop')

front_elem = self.array[0]

new_array = []

for elem in self.array[1:]:

new_array += [elem]

self.array = new_array

self.length -= 1

Now, let’s talk through each of the methods. The first three methods are sometimes refered to as dunder (double-underscore) or magic methods, and they are built into python’s class definition procedures. I use two of them - the initialization method tells us what to include and declare when instances of the class are created, while the representation of the class specifies how instances of the class will be represented. In other words, we can customize what happens when we print an Array object. Notice also that I define a length parameter, which will track how many items are in the array, so we know when the array is full.

The remaining methods use the operations we discuss earlier - pushing and popping, to both the front and back of the array. Notice that, whenever the operation deals with the front, all elements must be altered before the new array can be returned. Once we’ve defined such a class, we can test it. Here is how it works:

my_array = Array(size=10)

my_array.push_back(2)

my_array.push_front(1)

print(my_array)

for elem in my_array.array:

print(elem)

my_array.pop_back()

my_array.pop_front()

my_array.pop_back()

print(my_array)

> python arrays-lists.py

[1, 2], array of length 2

1

2

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "arrays-lists.py", line 76, in <module>

my_array.pop_back()

File "arrays-lists.py", line 36, in pop_back

raise Exception('Sorry, nothing to pop')

Exception: Sorry, nothing to pop

We can see that, after defining an array instance, and adding some items, the array displays in exactly the order you would think. The only trouble comes when we try to remove an item from an empty array. Per the code in the class definition, this raises an exception. I should mention that I ran this code directly from the command line, which produces the output you see here.

The Linked List

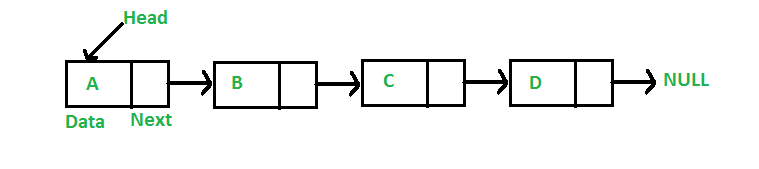

Now let’s look at a different structure - the linked list(more specifically, the single-linked list). Getting back to our baseball metaphor, suppose you could not find enough seats to sit side-by-side with your friends, so instead you each decide to find your own seat. How would you keep track of the group? Well first, everyone in the group should know who is first in your list. We call this first item/person the head, and no matter how many items are in the linked list, only one element can be the head. From there, each slot in memory contains 2 components: a key, which is just the person in that seat, and a pointer which indicates who is next in the list. The person at the end of the list has a pointer that points to None. In this way, the list is held together like links in a chain, where each person knows who is next. In a single linked list, the pointers only go one way - you do not know who came before you.

In a linked list, a single unit is called a node, and each node points to the next node in the list. So how does this affect the operations we described earlier? Well suppose you want to insert a node on the front of the list. Only three steps are necessary:

- Find the current head (front node).

- Make the inserted node the new head.

- Change the inserted node’s pointer to the old front node.

That’s it! And those same three steps are all that are required regardless of how big the list is. So in this case, pushing to the front is \( O(1) \). Now what about inserting to the back? Unfortunately linked lists are not indexed like arrays, so just finding the last item requires us to start at the beginning, and work our way node-to-node until we find the node whose pointer is None. Once there, we can just change the penultimate node’s pointer to None, and the list now excludes its last member. Because we had to traverse all the nodes, pushing to the back is \( O(N) \). Sometimes, we can speed this up by including a second indicator called a tail, which works just like the head, but tracks the last element in the list. In this case, the pushback operation would only be \( O(1) \).

What about deletion? Just like insertion, deleting from the front requires \( O(1) \), for the same reasons. Also, popping from the back is \( O(N) \) without a tail, but \( O(1) \) with a tail. What about finding/reading elements in the middle. Well, in order to do this (even with a tail), we have to start at one end of the list, and work our way inward until we find the item we’re searching for. This means that reading in linked lists is (at worst) \( O(N) \), tail or not.

Python does not have a base data structure similar to the linked list, but just like for arrays, let’s define our own. I’ll first define a separate class for an individual node, then work that class into the larger linked list blueprint:

class Node:

''' A node with a key (integer) and a pointer '''

def __init__(self, key):

self.key = key

self.next = None

def __repr__(self):

return self.key

class SingleLinkedList:

''' A single linked list with nodes connected by pointers '''

def __init__(self):

self.head = None

def __repr__(self):

node = self.head

nodes = []

while node is not None:

nodes.append(node.key)

node = node.next

nodes.append("None")

return " -> ".join(nodes)

def __iter__(self):

node = self.head

while node is not None:

yield node

node = node.next

def get_first(self):

''' Return the first node in the list '''

if self.head is not None:

return self.head.key

else: return None

def get_last(self):

''' Return the last node in the list (no tail) '''

last_node = self.head

current_node = last_node

while current_node is not None:

last_node = current_node

current_node = current_node.next

return last_node.key

def push_front(self, key):

''' Add a new node to the front of the list '''

new_node = Node(key)

new_node.next = self.head

self.head = new_node

def push_back(self, key):

''' Add a new node to the back of the list '''

new_node = Node(key)

old_last = self.get_last()

old_last.next = new_node

def pop_back(self):

''' Remove and return the back node '''

current_node = self.head

next_node = current_node.next

# As long as the next node is not the last

while next_node.next is not None:

current_node = current_node.next

next_node = current_node.next

# Change Pointer on Current node to None

current_node.next = None

# Return next (last) node

return next_node.key

def pop_front(self):

'''Remove and return the front node (key)'''

front_node = self.head

self.head = front_node.next

front_node.next = None

return front_node.key

Notice how we have to follow the list from beginning to end (I use a while loop) whenever we want to operate on the end of the list. The magic methods for this class are almost identical to the ones I defined for the Array class, however I include a third one here. The iteration method turns our linked list into an iterable object, meaning we can now loop through nodes in the list if we want to. So how does the above code work? We can see by executing some of our methods on a class instance:

my_list = SingleLinkedList()

my_list.push_front("A")

my_list.push_front("B")

my_list.push_back("C")

print(my_list)

my_list.pop_back()

print(my_list)

> python arrays-lists.py

B -> A -> C -> None

B -> A -> None

We can see that the output is now formatted very nicely, thanks to the __repr__ method. Overall, the linked list is a very useful data structure, and a large linked-list is more likely to fit in memory than an array of similar size.

Note that there are Double Linked lists, which contain pointers to both the next and previous nodes in the list. Reading in these types of lists becomes much faster, though there are a few more operations per node required by the machine (though in terms of big-O notation this has no effect). The use of nodes and pointers, which are also called directed edges, form the basis of a more general structure called a graph. I won’t go into detail about how graphs work, but they are the basis for many of the most efficient discrete algorithms used today.

Conclusion

There was a lot of information in this post, but I think the differences between Arrays and Linked-lists are best summarized in a simple table:

| Operation \ Data Structure | Array | L-List |

|---|---|---|

| Read | O(1) | O(N) |

| Push Front | O(N) | O(1) |

| Push Back | O(1) | O(1) |

| Pop Front | O(N) | O(1) |

| Pop Back | O(1) | O(N) |

Overall, arrays are better at reading/retrieving elements, but can be difficult to fit in memory when they are large. Linked-lists are better for insertion/ deletion, but are not great at reading elements. Which one to use depends on your application. Just keep in mind there are always such tradeoffs, and no data structure is universally better than others.

Further Reading

-

This article on linked lists is very good, and also includes a few other structures, like stacks and queues.

-

Grokking Algorithms is an excellent book, with a chapter dedicated to arrays and linked lists.

-

Algorithm Design by Kleinberg and Tardos is one of the leading texts on Algorithms and Data Structures.